Muybridge claimed that he first employed

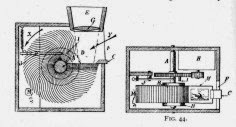

this mechanism, which he called a zoopraxiscope, in the fall of 1879, at Sanford's house. A

subsequent demonstration of the projector at Marey's studio in 1881 was

described in Parisian news- papers. A spectacular demonstration at the Royal

Institution in London

the following spring brought wide- spread notices in the scientific press.

In 1883 he

returned to America and

lectured with his zoopraxiscope in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Largely at the instigation of the painter, Thomas Eakins, who had conducted

similar photographic experiments, he was invited to continue his work in Philadelphia under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania.

Here, he radically improved his technique. He used dry plates, specially

sensitized by the Cramer Dry Plate Company.

In 1883 he

returned to America and

lectured with his zoopraxiscope in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Largely at the instigation of the painter, Thomas Eakins, who had conducted

similar photographic experiments, he was invited to continue his work in Philadelphia under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania.

Here, he radically improved his technique. He used dry plates, specially

sensitized by the Cramer Dry Plate Company. Three batteries of twelve cameras each were equipped with custom-made //2.5 lenses. The shutters were released by an im- proved synchronizer, which he called the "electro-expositor," patented in 1883.

The shutters consisted of two sliding

members; each pierced with a hole the size of the lens. One of these shutters

was pulled upwards by a spring, the other was pulled downwards. In the course

of their motion, the two holes coincided for a fraction of a second opposite

the lens. Both shutters were released by a simple catch, actuated by an

electromagnet.

The cameras could be arranged to take

twenty-four successive exposures, or three sets of twelve exposures

simultaneously from three points of view. The shortest possible exposure was

estimated to be 1/6000 of a second. But Muybridge remarked: "A knowledge

of the duration of the exposure was in this investigation of no value, and

scarcely a matter of curiosity, the aim being to give as long an expo- sure as

the rapidity of the action would permit."

The cameras could be arranged to take

twenty-four successive exposures, or three sets of twelve exposures

simultaneously from three points of view. The shortest possible exposure was

estimated to be 1/6000 of a second. But Muybridge remarked: "A knowledge

of the duration of the exposure was in this investigation of no value, and

scarcely a matter of curiosity, the aim being to give as long an expo- sure as

the rapidity of the action would permit."

A little later Muybridge designed a

portable camera, eighteen inches square and four feet long. It was

fitted with thirteen matched lenses, one of which served as a finder. Three

plates 12 inches long and 3 inches wide were put into specially designed

holders, which were divided into twelve compartments. The

"electro-expositor" and the multiple plate holder simplified the

technique; it was no longer necessary to stretch two dozen threads across the

track or to lead two dozen plate holders for each "take."

From the negatives of his new camera,

positives were printed on glass. These in turn were trimmed and assembled in

various combinations and a master negative printed from which photogravure

plates were made. Seven hundred and eighty-one such plates, each over 11 X 14 inches,

were made. The prints from them were published by the University of Pennsylvania

in 1887 and sold by subscription. Few cared, however, to purchase the complete

set of Animal Locomotion comprising eleven hugo folio volumes and

costing five-hundred dollars.

From the negatives of his new camera,

positives were printed on glass. These in turn were trimmed and assembled in

various combinations and a master negative printed from which photogravure

plates were made. Seven hundred and eighty-one such plates, each over 11 X 14 inches,

were made. The prints from them were published by the University of Pennsylvania

in 1887 and sold by subscription. Few cared, however, to purchase the complete

set of Animal Locomotion comprising eleven hugo folio volumes and

costing five-hundred dollars.

The subjects of these prints are varied

and numerous, with about half representing animals. In addition to horses,

there are elephants, antelopes, and other wild animals borrowed from the

Philadelphia Zoo. The remaining and more interesting plates are studies of men

and women in action. The most unusual plates are studies of ordinary action -a

girl climbing stairs, a mother lifting a child, a woman carrying a pail of

water, masons building a brick wall, workmen sawing wood. Muybridge intended

the photographs to be helpful to artists, to be a kind of dictionary of the

human figure.

Under the

auspices of the U.S. Bureau of Education, he ran a "Zoopraxographical

Hall" at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. He clearly explained the nature of

this exhibition in a booklet issued for visitors: "In the presentation of

a Lecture on Zoopraxography the course usually adopted is to project, much

larger than the size of life, upon a screen a series of the most important

phases of some act of animal locomotion, which are analytically described.

These successive phases are then combined in the zoopraxiscope which is set in

motion, and a reproduction of the original movement of life is distinctly

visible to the audience."

Under the

auspices of the U.S. Bureau of Education, he ran a "Zoopraxographical

Hall" at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. He clearly explained the nature of

this exhibition in a booklet issued for visitors: "In the presentation of

a Lecture on Zoopraxography the course usually adopted is to project, much

larger than the size of life, upon a screen a series of the most important

phases of some act of animal locomotion, which are analytically described.

These successive phases are then combined in the zoopraxiscope which is set in

motion, and a reproduction of the original movement of life is distinctly

visible to the audience."

Another attraction at the World's Fair was Edison's peephole moving-picture machine, the kinetoscope. It was a direct descendant of the zoopraxiscope and Edison, in a letter dated 1925 to the Society of Motion-Picture Engineers, wrote that the germ of his idea for moving' pictures "came from a little toy called the zoetrope and the work of Muybridge, Marey, and others."

Muybridge's work in the synthesis of

motion was soon forgotten. He was the first to admit that his technique had

been superseded, and to give credit to Edison

for his perfection of the zoopraxiscope.

The awkward and expensive folio plates of

Animal Locomotion were republished' at the turn of the

century with halftone reproductions in volumes of a more convenient size and

more modest price, under the titles Animals in Motion and The

Human Figure in Motion. These books are still in demand by art

students.

Muybridge passed the last years of his

life in England and died in

his native Kingston-on- Thames

in 1904.

No comments:

Post a Comment